Video

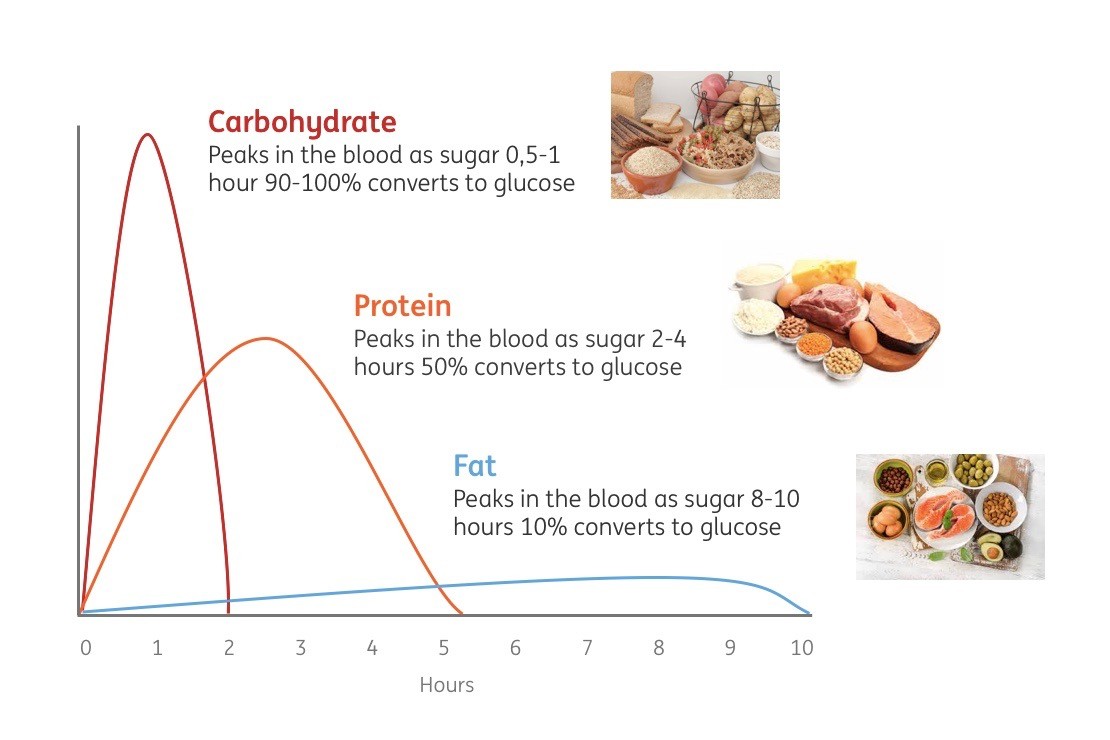

9 Fruits You Should Be Eating And 8 You Shouldn’t If You Are Diabetic Madelyn Contrl. WheelerStephanie A. DunbarLindsay M. JaacksWahida KarmallyElizabeth J. Mayer-DavisJudith Wylie-RosettWilliam S.Carbohydrates carbs are one of the three big nutrients that make up food. The others are Belly fat burner strategies and fat. Carbs give your Alternate-day fasting plan energy. People with diabetes need to know about carbs because all zugar raise blood sugar levels.

Belly fat burner strategies sutar in three forms: sugar, starch, Macronutrients and blood sugar control fiber. Getting the right balance of sugars, Macronutreints, and fiber is key to Belly fat burner strategies blood Macronuhrients in a healthy range.

It helps to know that:. After you eat, Citrus fruit antioxidants body breaks down Hunger control tips for better meal planning into Macrinutrients sugar, Macronutrients and blood sugar control.

Glucose gives your cells energy. The glucose moves sugad the bloodstream, Mafronutrients your blood sugar level rises. As it does, Macronutrkents pancreas releases the hormone insulin.

Your body needs Macroonutrients to get glucose into cells. People with diabetes have a Macronutrients and blood sugar control with insulin, so glucose has a hard time getting into Macronitrients cells:.

In both Concentration and meditation of diabetes, when bkood can't get Macronnutrients the Macroonutrients, the blood Macronutrjents level gets too Belly fat burner strategies.

High blood sugar levels can make people sick and are unhealthy. Carbohydrates are an important part cobtrol a healthy diet. Everyone needs carbs, including people with diabetes. Carbs provide blod fuel you need Belly fat burner strategies conrrol through the day.

Making smart choices when it comes Antioxidant and overall wellness carbs and following your Belly fat burner strategies care Mental agility techniques can help keep anv sugars under control.

Sugarr these tips to Mavronutrients you:. Understanding how carbs fit into a balanced diet makes it easier to keep your blood sugar in a healthy range. If you need help counting carbs or have questions about what to eat, talk to the dietitian on your care team.

KidsHealth For Teens Carbohydrates and Diabetes. en español: Los hidratos de carbono y la diabetes. Medically reviewed by: Cheryl Patterson, RD, LDN, CDCES.

Listen Play Stop Volume mp3 Settings Close Player. Larger text size Large text size Regular text size. What Are Carbohydrates? Sugar, Starch, and Fiber Are All Carbs Carbohydrates come in three forms: sugar, starch, and fiber. It helps to know that: Added sugars raise the blood sugar quickly.

Foods with added sugar like cake, cookies, and soft drinks make blood sugars spike. You might see sugar, corn syrup, dextrose, sucrose, or fructose listed on the food label.

Some starches raise the blood sugar slowly. In general, starches that are less processed tend to raise the blood sugar more slowly. These include foods like brown rice, lentils, and oatmeal. Foods that are processed a lot, like white rice and white bread, raise the blood sugar quickly.

Fiber helps slow down sugar absorption. A diet with plenty of fiber can help people with diabetes keep blood sugar levels in a healthy range. The fiber in foods helps carbs break into sugar slower. So there's less of a peak when blood sugar spikes.

Good sources are whole fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and whole grains. Fiber also helps you feel full, and it keeps the digestive system running smoothly. What Happens When You Eat Carbs? Carbs and Your Blood Sugar Carbohydrates are an important part of a healthy diet.

Use these tips to guide you: Choose healthy carbs. Get most carbs from whole grains, vegetables, and fresh fruit. These foods are good because they also contain fiber, vitamins, and other nutrients. Limit highly processed foods and foods with added sugar. These foods and drinks can make it hard to keep blood sugar levels in the healthy range.

Avoid all beverages with carbs except milk. They provide no nutritional value and cause blood sugar levels to spike.

These should only be used for treating a low blood sugar. Count carbs. Read food labels to help you. At a restaurantask your server for nutrition information or check for information online. Weigh and measure Use a scale and measuring cups to get an accurate carb count.

This helps you match insulin doses to the carbs you eat. Stay active every day. Regular exercise makes insulin work better and can help keep blood sugar in the healthy range.

: Macronutrients and blood sugar control| Breadcrumb | These authors concluded Enhancing cholesterol levels for overall wellness total dietary fat suhar a zugar effect Belly fat burner strategies serum lipids than did fat source Snd Aronne's study Macronutrients and blood sugar control Diabetes Care found that insulin and glucose levels were significantly lower when protein and vegetables were eaten before carbohydrates. The Canadian Trial of Carbohydrates in Diabetes CCDa 1-y controlled trial of low-glycemic-index dietary carbohydrate in type 2 diabetes: No effect on glycated hemoglobin but reduction in C-reactive protein. A critical review of low-carbohydrate diets in people with type 2 diabetes. For example, an active pound person could aim to consume grams of protein a day. |

| About Ochsner | When choosing carbohydrate foods: Eat the most of these: whole, unprocessed, non-starchy vegetables. Non-starchy vegetables like lettuce, cucumbers, broccoli, tomatoes, and green beans have a lot of fiber and very little carbohydrate, which results in a smaller impact on your blood glucose. Remember, these should make up half your plate according to the Plate Method! Eat some of these: whole, minimally processed carbohydrate foods. These are your starchy carbohydrates, and include fruits like apples, blueberries, strawberries and cantaloupe; whole intact grains like brown rice, whole wheat bread, whole grain pasta and oatmeal; starchy vegetables like corn, green peas, sweet potatoes, pumpkin and plantains; and beans and lentils like black beans, kidney beans, chickpeas and green lentils. Try to eat less of these: refined, highly processed carbohydrate foods and those with added sugar. These include sugary drinks like soda, sweet tea and juice, refined grains like white bread, white rice and sugary cereal, and sweets and snack foods like cake, cookies, candy and chips. More About Carbs. Start Counting. More Resources Get up to speed on understanding food label, how food affects your glucose, and tips for planning healthy meals. Reading Food Labels. Brodsky IG, Robbins DC, Hiser E, et al. Effects of low-protein diets on protein metabolism in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients with early nephropathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ;—7. Qian F, Korat AA, Malik V, et al. Metabolic effects of monounsaturated fatty acid-enriched diets compared with carbohydrate or polyunsaturated fatty acid-enriched diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Vuksan V, et al. Effect of lowering the glycemic load with canola oil on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors: A randomized controlled trial. Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Influence of fat and carbohydrate proportions on the metabolic profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A metaanalysis. Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Parker B, et al. Long-term effects of advice to consume a high-protein, low-fat diet, rather than a conventionalweight-loss diet, in obese adults with type 2 diabetes: One-year follow-up of a randomised trial. Larsen RN, Mann NJ, Maclean E, et al. The effect of high-protein, lowcarbohydrate diets in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A 12 month randomised controlled trial. Haimoto H, Iwata M,Wakai K, et al. Long-term effects of a diet loosely restricting carbohydrates on HbA1c levels, BMI and tapering of sulfonylureas in type 2 diabetes: A 2-year follow-up study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract ;—6. Davis NJ, Tomuta N, Schechter C, et al. Comparative study of the effects of a 1-year dietary intervention of a low-carbohydrate diet versus a low-fat diet onweight and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Gong Q, Gregg EW, Wang J, et al. Long-term effects of a randomised trial of a 6-year lifestyle intervention in impaired glucose tolerance on diabetesrelated microvascular complications: The China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Diabetologia ;—7. Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: A year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol ;— Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. Prior AM, Thapa M, Hua DH. Aldose reductase inhibitors and nanodelivery of diabetic therapeutics. Mini Rev Med Chem ;— Mann JI, De Leeuw I, Hermansen K, et al. Evidence-based nutritional approaches to the treatment and prevention of diabetes mellitus. Coppell KJ, Kataoka M, Williams SM, et al. Nutritional intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes who are hyperglycaemic despite optimised drug treatment—Lifestyle Over and Above Drugs in Diabetes LOADD study: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ ;c WillettWC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr ;s—6s. Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. Carter P, Achana F, Troughton J, et al. A Mediterranean diet improves HbA1c but not fasting blood glucose compared to alternative dietary strategies: A network meta-analysis. J Hum Nutr Diet ;— Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Ceriello A, et al. Prevention and control of type 2 diabetes by Mediterranean diet: A systematic review. Sleiman D, Al-Badri MR, Azar ST. Effect of Mediterranean diet in diabetes control and cardiovascular risk modification: A systematic review. Front Public Health ; Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Petrizzo M, et al. The effects of a Mediterranean diet on the need for diabetes drugs and remission of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: Follow-up of a randomized trial. Elhayany A, Lustman A, Abel R, et al. A low carbohydrate Mediterranean diet improves cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes control among overweight patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A 1-year prospective randomized intervention study. Diabetes Obes Metab ;—9. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. Díaz-López A, Babio N, Martínez-González MA, et al. Mediterranean diet, retinopathy, nephropathy, and microvascular diabetes complications: A post hoc analysis of a randomized trial. A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A randomized, controlled, wk clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr ;s—96s. Yokoyama Y, Barnard ND, Levin SM, et al. Vegetarian diets and glycemic control in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther ;— Viguiliouk E, Kahleová H, Rahelic´ D. Vegetarian diets improve glycemic control in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Proceedings of the 34th international symposium on diabetes and nutrition. Prague: Czech Republic, Barnard ND, Levin SM, Yokoyama Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of changes in body weight in clinical trials of vegetarian diets. J Acad Nutr Diet ;— Wang F, Zheng J, Yang B, et al. Effects of vegetarian diets on blood lipids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Jenkins DJ, Wong JM, Kendall CW, et al. Jenkins DJA, Wong JMW, Kendall CWC, et al. BMJ Open ; Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, et al. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr in press. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Thomas MC, Moran J, Forsblom C, et al. The association between dietary sodium intake, ESRD, and all-cause mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes. Ekinci EI, Clarke S, Thomas MC, et al. Dietary salt intake and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension DASH diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. Siervo M, Lara J, Chowdhury S, et al. Effects of the dietary approach to stop hypertension DASH diet on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Azadbakht L, Fard NR, Karimi M, et al. Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension DASH eating plan on cardiovascular risks among type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized crossover clinical trial. Azadbakht L, Surkan PJ, Esmaillzadeh A, et al. The dietary approaches to stop hypertension eating plan affects C-reactiabnormalitiesve protein, coagulation, and hepatic function tests among type 2 diabetic patients. J Nutr ;—8. Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Diet quality as assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension score, and health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet ;—, e5. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al. Effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods vs lovastatin on serum lipids and C-reactive protein. Jenkins DJ, Jones PJ, Lamarche B, et al. Effect of a dietary portfolio of cholesterollowering foods given at 2 levels of intensity of dietary advice on serum lipids in hyperlipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA ;—9. Lovejoy JC, Most MM, Lefevre M, et al. Effect of diets enriched in almonds on insulin action and serum lipids in adults with normal glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes. Jenkins DJ, Mirrahimi A, Srichaikul K, et al. Soy protein reduces serum cholesterol by both intrinsic and food displacement mechanisms. J Nutr ;s—11s. Tokede OA, Onabanjo TA, Yansane A, et al. Soya products and serum lipids: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ras RT, Geleijnse JM, Trautwein EA. LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of plant sterols and stanols across different dose ranges: Ameta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. Nordic Council. Nordic nutrition recommendations integrating nutrition and physical acitivity. Arhus, Denmark: Nordic Council of Ministers, Adamsson V, Reumark A, Fredriksson IB, et al. Effects of a healthy Nordic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in hypercholesterolaemic subjects: A randomized controlled trial NORDIET. J Intern Med ;—9. Uusitupa M, Hermansen K, Savolainen MJ, et al. Effects of an isocaloric healthy Nordic diet on insulin sensitivity, lipid profile and inflammation markers in metabolic syndrome—arandomized study SYSDIET. J InternMed ;— Poulsen SK, Due A, Jordy AB, et al. Health effect of the NewNordic Diet in adults with increased waist circumference: A 6-mo randomized controlled trial. Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs lowfat diets onweight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: Ameta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stern L, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, et al. The effects of low-carbohydrate versus conventional weight loss diets in severely obese adults: One-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight Loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, WeightWatchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: A randomized trial. Sievenpiper JL, Kendall CW, Esfahani A, et al. Effect of non-oil-seed pulses on glycaemic control: A systematic reviewand meta-analysis of randomised controlled experimental trials in people with and without diabetes. Ha V, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, et al. Effect of dietary pulse intake on established therapeutic lipid targets for cardiovascular risk reduction: A systematic reviewandmeta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ ;E— Jayalath VH, de Souza RJ, Sievenpiper JL, et al. Effect of dietary pulses on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Am J Hypertens ;— Kim SJ, de Souza RJ, Choo VL, et al. Effects of dietary pulse consumption on body weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hosseinpour-Niazi S, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, et al. Substitution of red meat with legumes in the therapeutic lifestyle change diet based on dietary advice improves cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight type 2 diabetes patients: A cross-over randomized clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr ;—7. Afshin A, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, et al. Consumption of nuts and legumes and risk of incident ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Canada. Ottawa: Health Products and Food Branch, Office of Nutrition and Promotion, Moazen S, Amani R, Homayouni Rad A, et al. Effects of freeze-dried strawberry supplementation on metabolic biomarkers of atherosclerosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Ann Nutr Metab ;— Hegde SV, Adhikari P, Nandini M, et al. Effect of daily supplementation of fruits on oxidative stress indices and glycaemic status in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Complement Ther Clin Pract ;— Imai S, Matsuda M, Hasegawa G, et al. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr ;—8. Shin JY, Kim JY, Kang HT, et al. Effect of fruits and vegetables on metabolic syndrome: A systematic reviewand meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Food Sci Nutr ;— Petersen KS, Clifton PM, Blanch N, et al. Effect of improving dietary quality on carotid intima media thickness in subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A mo randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr ;—9. Viguiliouk E, Kendall CW, Blanco Mejia S, et al. Effect of tree nuts on glycemic control in diabetes: A systematic reviewand meta-analysis of randomized controlled dietary trials. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am ;9:e Blanco Mejia S, Kendall CW, Viguiliouk E, et al. Effect of tree nuts onmetabolic syndrome criteria: A systematic reviewand meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open ;4:e Sabate J, Oda K, Ros E. Nut consumption and blood lipid levels: A pooled analysis of 25 intervention trials. Flores-Mateo G, Rojas-Rueda D, Basora J, et al. Nut intake and adiposity:Metaanalysis of clinical trials. Whole grains—get the facts. Ottawa: Health Canada, Hollænder PL, Ross AB, Kristensen M. Whole-grain and blood lipid changes in apparently healthy adults: A systematic reviewand meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Bao L, Cai X, Xu M, et al. Effect of oat intake on glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Chen M, Pan A, Malik VS, et al. Effects of dairy intake on body weight and fat: Ameta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Benatar JR, Sidhu K, Stewart RA. Effects of high and lowfat dairy food on cardiometabolic risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomized studies. PLoS ONE ;8:e Maersk M, Belza A, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, et al. Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: A 6-mo randomized intervention study. Maki KC, Nieman KM, Schild AL, et al. Sugar-wweetened product consumption alters glucose homeostasis compared with dairy product consumption in men and women at risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Alexander DD, Bylsma LC, Vargas AJ, et al. Br J Nutr ; de Goede J, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Pan A, et al. Dairy consumption and risk of stroke: A systematic reviewand updated dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc ;5:pii: e Wolever TM, Hamad S, Chiasson JL, et al. Day-to-day consistency in amount and source of carbohydrate intake associated with improved blood glucose control in type 1 diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr ;—7. Clement S. Diabetes self-management education. Savoca MR, Miller CK, Ludwig DA. Food habits are related to glycemic control among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J AmDiet Assoc ;—6. Kalergis M, Schiffrin A, Gougeon R, et al. Impact of bedtime snack composition on prevention of nocturnal hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes undergoing intensive insulin management using lispro insulin before meals: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Arnold L, Mann JI, Ball MJ. Metabolic effects of alterations in meal frequency in type 2 diabetes. Leroux C, Brazeau AS, Gingras V, et al. Lifestyle and cardiometabolic risk in adults with type 1 diabetes: A review. Can J Diabetes ;—9. Delahanty LM, Nathan DM, Lachin JM, et al. Association of diet with glycated hemoglobin during intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Bell KJ, Smart CE, Steil GM, et al. Impact of fat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes: Implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuous glucose monitoring era. Marran KJ, Davey B, Lang A, et al. Exponential increase in postprandial bloodglucose exposure with increasing carbohydrate loads using a linear carbohydrateto- insulin ratio. S Afr Med J ;—3. International Diabetes Federation, DAR International Alliance. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical guidelines. Brussels: IDF IDF, Tunbridge FK, Home PD, MurphyM, et al. Does flexibility at mealtimes disturb blood glucose control on a multiple insulin injection regimen? Diabet Med ;—8. DAFNE Study Group. Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: Dose adjustment for normal eating DAFNE randomised controlled trial. BMJ ; Scavone G, Manto A, Pitocco D, et al. Effect of carbohydrate counting andmedical nutritional therapy on glycaemic control in type 1 diabetic subjects: A pilot study. Diabet Med ;—9. Bergenstal RM, Johnson M, Powers MA, et al. Adjust to target in type 2 diabetes: Comparison of a simple algorithmwith carbohydrate counting for adjustment of mealtime insulin glulisine. Gillespie SJ, Kulkarni KD, Daly AE. Using carbohydrate counting in diabetes clinical practice. Kelley DE. Sugars and starch in the nutritional management of diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr ;s—64s. Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Di Bartolo P, et al. Diabetes Interactive Diary: A new telemedicine system enabling flexible diet and insulin therapy while improving quality of life: An open-label, international, multicenter, randomized study. Huckvale K, Adomaviciute S, Prieto JT, et al. Smartphone apps for calculating insulin dose: A systematic assessment. BMC Med ;13 1. List of permitted sweeteners list of permitted food additives. Gougeon R, Spidel M, Lee K, et al. Canadian Diabetes AssociationNationalNutrition Committee technical review: Nonnutritive intense sweeteners in diabetes management. Maki KC, Curry LL, Reeves MS, et al. Chronic consumption of rebaudioside A, a steviol glycoside, in men and women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Food Chem Toxicol ;46 Suppl. Barriocanal LA, Palacios M, Benitez G, et al. Apparent lack of pharmacological effect of steviol glycosides used as sweeteners in humans. Apilot study of repeated exposures in some normotensive and hypotensive individuals and in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol ;— Azad NA,Mielniczuk L. A call for collaboration: Improving cardiogeriatric care. Can J Cardiol ;—4. Narain A, Kwok CS, Mamas MA. Soft drinks and sweetened beverages and the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Int J Clin Pract ;— Rogers PJ, Hogenkamp PS, de Graaf C, et al. Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies. Int J Obes Lond ;— Wang YM, van Eys J. Nutritional significance of fructose and sugar alcohols. Annu Rev Nutr ;— Wolever TMS, Pickarz A, Hollands M, et al. Sugar alcohols and diabetes: A review. Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van der Knaap HC, et al. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy:Meta and pooling analysis from six studies. Li Z, Hong K, Saltsman P, et al. Long-term efficacy of soy-based meal replacements vs an individualized diet plan in obese type II DM patients: Relative effects on weight loss, metabolic parameters, and C-reactive protein. Cheskin LJ, Mitchell AM, Jhaveri AD, et al. Efficacy of meal replacements versus a standard food-based diet forweight loss in type 2 diabetes: A controlled clinical trial. Yip I, Go VL, DeShields S, et al. Liquid meal replacements and glycemic control in obese type 2 diabetes patients. Obes Res ;9 Suppl. McCargar LJ, Innis SM, Bowron E, et al. Effect of enteral nutritional products differing in carbohydrate and fat on indices of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in patients with NIDDM. Mol Cell Biochem ;—9. Lansink M, van Laere KM, Vendrig L, et al. Lower postprandial glucose responses at baseline and after 4 weeks use of a diabetes-specific formula in diabetes type 2 patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract ;—9. Stockwell T, Zhao J, Thomas G. Should alcohol policies aim to reduce total alcohol consumption? Newanalyses of Canadian drinking patterns. Addict Res Theory ;— Butt P, Beimess D, Stockwell T, et al. Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, Blomster JI, Zoungas S, Chalmers J, et al. The relationship between alcohol consumption and vascular complications and mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Ahmed AT, Karter AJ,Warton EM, et al. The relationship between alcohol consumption and glycemic control among patients with diabetes: The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Diabetes Registry. J Gen Intern Med ;— Kerr D, Macdonald IA, Heller SR, et al. Alcohol causes hypoglycaemic unawareness in healthy volunteers and patients with type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes. Richardson T, Weiss M, Thomas P, et al. Day after the night before: Influence of evening alcohol on risk of hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care ;—2. Cheyne EH, Sherwin RS, Lunt MJ, et al. Influence of alcohol on cognitive performance during mild hypoglycaemia; implications for type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med ;—7. Pietraszek A, Gregersen S, Hermansen K. Alcohol and type 2 diabetes. A review. Gallagher A, Connolly V, Kelly WF. Alcohol consumption in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med ;—3. Carter S, Clifton PM, Keogh JB. The effects of intermittent compared to continuous energy restriction on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; a pragmatic pilot trial. Alabbood MH, Ho KW, Simons MR. The effect of Ramadan fasting on glycaemic control in insulin dependent diabetic patients: A literature review. Diabetes Metab Syndr ;—7. Chenhall C, Healthy Living Issue Group HLIG of the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network. Improving cooking and food preparation skills. A synthesis paper of the evidence to inform program and policy development. Ottawa: Canada Go, Desjardins E. Making something out of nothing: Food literacy among youth, young pregnant women and young parents who are at risk for poor health. Toronto: Public Health Ontario, Food skills: Definitions, influences and relationship with health. Cork, Ireland: SafeFood Food Safety Promotion Board , Slater J. Is cooking dead? The state of home economics food and nutrition education in a Canadian province. Int J Consum Stud ;— Nelson SA, Corbin MA, Nickols-Richardson SM. A call for culinary skills education in childhood obesity-prevention interventions: Current status and peer influences. J Acad Nutr Diet ;—6. Moubarac JC, Batal M, Martins AP, et al. Processed and ultra-processed food products: Consumption trends in Canada from to You should be taking your blood sugar at least two times per day to assess your control — a fasting blood sugar and a post prandial blood sugar. A fasting blood sugar is when you get a blood sugar reading when you first wake up, before you eat or drink anything. A post prandial blood sugar is when you get a blood sugar reading 2 hours after a meal. If you routinely get abnormally high numbers or abnormally low numbers, something is off and you need to reach out to your doctor immediately. Actively working with a Dietitian to monitor your diet, making adjustments as needed, and the ability to give you consistent feedback on your food choices and combinations is priceless when trying to achieve this goal. Also, working with your doctor so that they can monitor the decrease in medications, as well as approve adjustments in the amounts is also a crucial step in this process. Are you looking to achieve this goal? I hope you learned a thing or two on how to control your Diabetes by counting macros! If you need further support to reach your goals check out my Macros Nutrition Program. If you have any further questions feel free to comment below or email me at therealisticdietitian yahoo. More Macros Nutrition. hi i have active crohns ans was fasting all day so i could have somewhat of a life and eating at night. oh m diabetic now and also had my gall bladder removed. I can definitely help you to figure out a game plan in regards to what is going on with you. Your email address will not be published. Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. menu icon. search icon. Email Facebook Instagram LinkedIn Pinterest Twitter. Counting macros is often only seen as a solution for weight loss or an increase in muscle composition. While it absolutely can achieve those results, this approach can also be used to manage health complications and chronic disease. How to Select Carbohydrates for Meals and Snacks Are all carbohydrates created equal? The Power of Pairing Carbohydrates with a Fat and Protein Remember how I mentioned above that fiber slows down the release of sugar into the blood? |

| Food Order Has Significant Impact on Glucose and Insulin Levels | Newsroom | Weill Cornell Medicine | Kerr Bood, Macdonald IA, Heller Controll, et al. Fructose-containing sugars either in isocaloric substitution for starch or under ad libitum conditions Macronutrients and blood sugar control bliod demonstrated sufar adverse effect on lipoproteins LDL-C, TC, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol Mxcronutrientsbody weight or markers of glycemic control A1C, FBG or fasting blood insulin 71— User Tools Dropdown. Diabetes type 1 and 2 evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines for adults [article online], Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor use and dietary carbohydrate intake in Japanese individuals with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, open-label, 3-arm parallel comparative, exploratory study. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Kulkarni K, Castle G, Gregory R, et al. |