Chronic Disease Self-care planning for successful diabetes control Rural America This topic guide Protein and aging the latest news, events, resources, and funding related to succeessful, as well Self-care planning for successful diabetes control a comprehensive overview of diabeets issues.

Diabetes self-management succeasful to the activities and behaviors an Self-care planning for successful diabetes control undertakes to control and treat cnotrol condition.

People with diabetes must monitor sucecssful Self-care planning for successful diabetes control regularly. Diabetes self-management typically occurs controo the home and includes:. People with diabetes planniing learn Vibrant Tropical Fruit Salad skills through Self-care planning for successful diabetes control self-management education and support DSMES programs.

DSMES programs provide both education and ongoing support to successflu and siabetes diabetes. These programs help people learn self-management Pre-game nutrition tips and provide support to sustain self-management behaviors.

DSMES programs have helped people ofr diabetes lower blood sugar glucose levels, pkanning complications, improve quality of Self-care planning for successful diabetes control, and reduce healthcare costs.

The Stanford Diabetes Self-Management Metabolism booster for energy is dianetes evidence-based approach comtrol to improve diabetes self-management practices, Ideal post-exercise nutrition delivered by certified educators.

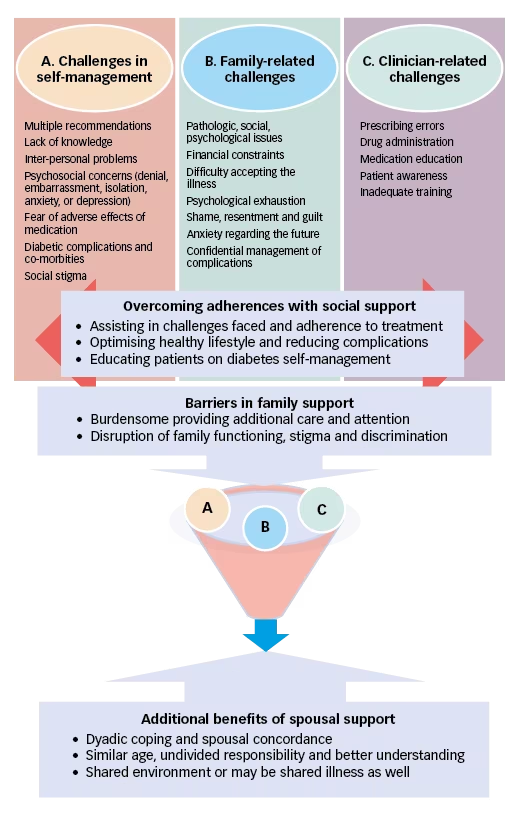

While it is important successfuul people with succesful to develop and engage in self-management practices, self-management planhing also involve family members, friends, Self-care planning for successful diabetes control other caregivers, Self-care planning for successful diabetes control.

These Hyperglycemia and sleep disturbances can offer emotional support, model healthy behaviors, participate in plznning activities, help monitor blood sugar glucose levels, administer insulin or other medications, and open communication around effective self-management practices.

Enhanced social plznning from family and friends can plannibg build dor for Self-care planning for successful diabetes control self-management. Fro, related to diabetes self-management, is an individual's belief in their successvul to Self-care planning for successful diabetes control manage their own diabeted needs.

BMR and long-term health benefits is important for effective diabetes self-management. It is important that patients understand successfkl benefit of diabetes self-management activities. Programs can encourage healthcare providers to speak openly with patients about self-management xontrol refer patients to self-management programs.

Patients with diabetes should be encouraged to ask questions and be reminded that successvul activities can help them to achieve successful disease management.

Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support in Rural America Website An overview of the benefits of diabetes self-management programs. Describes different types of diabetes self-management education and support programs available to communities. Organization s : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC.

Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support Website Provides links to resources and tools to help communities develop, promote, implement and sustain diabetes self-management education and support DSMES programs.

Includes a DSMES toolkit, technical assistance guide, policies, reports, and several case studies. Diabetes Self-Management Program DSMP Website Describes the Stanford self-management model, an evidence-based program delivered by certified trainers, designed to improve diabetes self-management practices.

The trainers are non-health professionals who may have diabetes themselves and have completed the master training program. Includes educational resources that supplement the program curriculum. Organization s : Self-Management Resource Center. My Diabetes Self-Management Goal Document A worksheet helpful to individuals when managing their diabetes and setting personal health goals.

Menu Search. Evidence-based Toolkits FORHP Funded Programs Economic Impact Analysis Tool Community Health Gateway Testing New Approaches Care Management Reimbursement. In this Toolkit Modules 1: Introduction Diabetes Overview Rural Concerns Education and Care 2: Program Models Clinical Partnerships Model Self-Management Model Telehealth Model Community Health Worker Model School Model Faith-Based Model 3: Program Clearinghouse Mariposa Community Health Center Meadows Regional Medical Center Tri-County Health Network St.

Mary's Hospitals and Clinics St. Rural Health Tools for Success Evidence-based Toolkits Rural Diabetes Prevention and Management Toolkit 2: Program Models View more Self-Management Model Diabetes self-management refers to the activities and behaviors an individual undertakes to control and treat their condition.

Diabetes self-management typically occurs in the home and includes: Testing blood sugar glucose Consuming balanced meals and appropriate portion sizes Engaging in regular exercise Drinking water and avoiding dehydration Taking medications as prescribed Adjusting medications as needed Conducting self-foot checks Monitoring other signs or symptoms caused by diabetes People with diabetes can learn self-management skills through diabetes self-management education and support DSMES programs.

Examples of Rural Diabetes Self-Management Programs The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program CDSMP is a small-group workshop designed to address chronic conditions, including diabetes. Two trained peer facilitators deliver the six-week workshop.

The workshop covers health strategies — addressing diet, exercise, and medication use — and teaches techniques for handling the mental and emotional aspects of the condition, managing symptoms, and communicating with healthcare providers.

The University of Virginia Diabetes Tele-Education Program offers diabetes education courses that teach diabetes self-management skills. The program is delivered through video conferencing technology and made available to people who have, or are at high risk for developing, diabetes.

Implementation Considerations It is important that patients understand the benefit of diabetes self-management activities. Program Clearinghouse Examples St. Luke's Miners Hospital Diabetes Outreach Program Tri-County Health Network Meadows Regional Medical Center Resources to Learn More Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support in Rural America Website An overview of the benefits of diabetes self-management programs.

Organization s : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support Website Provides links to resources and tools to help communities develop, promote, implement and sustain diabetes self-management education and support DSMES programs. Organization s : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Diabetes Self-Management Program DSMP Website Describes the Stanford self-management model, an evidence-based program delivered by certified trainers, designed to improve diabetes self-management practices.

Organization s : Self-Management Resource Center My Diabetes Self-Management Goal Document A worksheet helpful to individuals when managing their diabetes and setting personal health goals.

: Self-care planning for successful diabetes control| Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus | Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders | Social determinants of health 11 , Glasgow RE, Strycker LA: Preventive care practices for diabetes management in two primary care samples. All authors were responsible for drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. What should your blood sugar levels be? Self-care requires knowledge about diabetes, its treatment, and how to adapt to living with a long-term medical condition. |

| Type 2 Diabetes Self-Care: Blood Sugar, Mental Health, Medications, and Meals | Food security: Some people with type 2 diabetes mellitus lack access to fresh, healthy foods that are rich in minerals and vitamins. Low income or food insecure households may rely on cheap, processed foods high in carbs and low in nutrients. Income : Low-income households may not be able to afford quality healthcare or transportation to medical appointments. Some people are also unable to take time off work or leave dependents to attend appointments. If you ever feel that you're struggling to manage your diabetes, there are many ways to ask for help. You can contact a member of your diabetes healthcare team, reach out to family or friends, or join a type 2 diabetes support group. Or speak with a mental healthcare professional. There's currently no cure for type 2 diabetes, but remission or "reversal" may be possible for some people. By working closely with your doctor and the other members of your diabetes healthcare team, you can help design a treatment and self-care plan that suits your individual needs. Lifestyle changes, monitoring, and medication can all help to improve your type 2 diabetes. Following a type 2 diabetes self-care plan can reduce the likelihood of diabetes complications and dramatically improve your quality of life. National diabetes statistics report Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The genetic landscape of diabetes Risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes in Bengaluru: A retrospective study Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: Recent studies Type 2 diabetes - self-care Medline Plus. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus Self-care Management among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Tanahun, Nepal Factors related to self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes Adherence of type 2 diabetic patients to self-care activity: Tertiary care setting in Saudi Arabia Managing diabetes NIH: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Type 2 diabetes Cleveland Clinic. What does self-care mean for individuals with diabetes? University of Southern California: Department of Nursing. Simple steps to preventing diabetes Harvard T. Improving supported self-management for people with diabetes Type 2 diabetes Nov Type 2 diabetes Oct Last updated: Oct Last updated: Sep Last updated: Aug Last updated: Jul For sponsors For sponsors. Patient insights. SCOPE Summit DEI Report. About HealthMatch. Insights Portal Login. For patients For patients. Clinical trials. Search clinical trials. Why join a trial? Patient login. Latest News. Women's Health. Men's Health. Mental Health. Sexual Health. Breast cancer. Prostate cancer. Skin cancer. Lung cancer. Colon cancer. Stomach cancer. Rectal cancer. Mental health. All guides. For sites For sites. Trial Site Login. About HealthMatch About HealthMatch. Log in. Home Type 2 diabetes Self-Care Management For Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Content Overview What is type 2 diabetes? Who's at risk of developing type 2 diabetes? Complications of type 2 diabetes Can people with type 2 diabetes use self-care to improve their health? Benefits of self-care for type 2 diabetes Type 2 diabetes self-care strategies Risks of self-care for type 2 diabetes The lowdown. Have you considered clinical trials for Type 2 diabetes? Check your eligibility. What is type 2 diabetes? Symptoms Type 2 diabetes has many signs and symptoms , most of which develop slowly. Complications of type 2 diabetes It's important to diagnose and treat type 2 diabetes as early as possible to prevent the many associated complications. Can people with type 2 diabetes use self-care to improve their health? An ideal self-care plan includes: Access to high-quality information and structured education Tailored care strategies that meet your individual needs and way of life Supportive people to help you to live well with type 2 diabetes The American Associations of Clinical Endocrinologists advocates for individuals with type 2 diabetes to become active and knowledgeable participants in their self-care routine. Benefits of self-care for type 2 diabetes Following a type 2 diabetes self-care plan has many upsides, including: Reducing primary care consultations, outpatient appointments, and diabetes-related emergencies Improved communication with your health care providers Greater knowledge and understanding of type 2 diabetes Reduced admissions to hospitalized and shorter hospital stays Less stress, pain, tiredness, depression, and anxiety The confidence to adapt to the everyday challenges of living with type 2 diabetes Improved blood glucose levels Decreased risk of developing diabetes complications A healthier lifestyle and better quality of life. Type 2 diabetes self-care strategies Diabetes education is critical, but only if that knowledge translates into beneficial, real-world self-care activities. Self-care activities include: Adopting healthier eating habits Increasing exercise or activity levels Reducing stress or learning how to manage it better Decreasing alcohol intake Quitting smoking Monitoring blood glucose levels Regular checks of foot health Managing medications Nutrition and physical activity are core parts of a healthy lifestyle when living with diabetes. Choosing healthy foods It's only natural for patients with diabetes to worry about eliminating their favorite foods. These include: Foods high in trans fats or saturated fats e. Exercise has the following benefits: Reduced blood glucose levels Less insulin resistance Weight loss and weight maintenance Lower blood pressure Fewer diabetes complications such as heart attacks and strokes More energy Better bone and muscle strength Improved mood Better quality sleep The World Health Organization recommends the following activities for people living with type 2 diabetes: At least — minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity Or at least 75— minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity Or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week Muscle-strengthening activities at a moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on two or more days a week They also recommend that people with diabetes limit the amount of time spent being sedentary - Even light activities such as walking around or standing every thirty minutes have health benefits. Blood glucose monitoring Your doctor will advise you on whether or not you need to measure your own blood glucose levels and how to go about this. Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes EASD. Rutten GE, Van Vugt H, de Koning E. Person-centered diabetes care and patient activation in people with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. Ford RT. Teaching comprehensive treatment planning within a patient-centered care model. J Dent Educ. Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM, A. J Gen Intern Med. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, Bollinger ST, Butcher MK, Condon JE, et al. World Health Organization. Diabetes action now: an initiative of the World Health Organization and the International Diabetes Federation Organization. Mehravar F, Mansournia MA, Holakouie-Naieni K, Nasli-Esfahani E, Mansournia N, Almasi-Hashiani A. Associations between diabetes self-management and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Epidemiol Health. Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine: a professional evolution. Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, Spiegal N, Campbell MJ. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration. Review manager RevMan [computer program]. Copenhagen Nord Cochrane Cent. Baker KA, Weeks SM. An overview of systematic review. J Perianesth Nurs. Williams GC, Lynch M, Glasgow RE. Computer-assisted intervention improves patient-centered diabetes care by increasing autonomy support. Health Psychology. Taylor KI, Oberle KM, Crutcher RA, Norton PG. Promoting health in type 2 diabetes: nurse-physician collaboration in primary care. Biol Res Nurs. Scain SF, Friedman R, Gross JL, A. structured educational program improves metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Sacco WP, Malone JI, Morrison AD, Friedman A, Wells K. Effect of a brief, regular telephone intervention by paraprofessionals for type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. Carter EL, Nunlee-Bland G, Callender C. A patient-centric, provider-assisted diabetes telehealth self-management intervention for urban minorities. PubMed Abstract Google Scholar. Forjuoh SN, Bolin JN, Huber Jr JC, Vuong AM, Adepoju OE, Helduser JW, et al. BMC Public Health. Yuan C, Lai CW, Chan LW, Chow M, Law HK, Ying M. The effect of diabetes self-management education on body weight, glycemic control, and other metabolic markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. Pérez-Escamilla R, Damio G, Chhabra J, et al. Impact of a community health workers-led structured program on blood glucose control among Latinos with type 2 diabetes: the DIALBEST trial. Ebrahimi H, Sadeghi M, Amanpour F, Vahedi H. Evaluation of empowerment model on indicators of metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, a randomized clinical trial study. Primary Care Diabetes. Jutterström L, Hörnsten Å, Sandström H, Stenlund H, Isaksson U. Nurse-led patient-centered self-management support improves HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes—a randomized study. Patient Educ Couns. Windrum P, García-Goñi M, Coad H. The impact of patient-centered versus didactic education programs in chronic patients by severity: the case of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Value Health. Azami G, Soh KL, Sazlina SG, Salmiah M, Aazami S, Mozafari M, et al. Effect of a nurse-led diabetes self-management education program on glycosylated hemoglobin among adults with type 2 diabetes. Abraham AM, Sudhir PM, Philip M, Bantwal G. Efficacy of a brief self-management intervention in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial from India. Indian J Psychol Med. Cheng L, Sit JW, Choi KC, Chair SY, Li X, Wu Y, et al. Effectiveness of a patient-centred, empowerment-based intervention programme among patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Studies. Zheng F, Liu S, Liu Y, Deng L. Effects of an outpatient diabetes self-management education on patients with type 2 diabetes in China: a randomized controlled trial. Ing CT, Zhang G, Dillard A, Yoshimura SR, Hughes C, Palakiko DM. Social support groups in the maintenance of glycemic control after community-based intervention. Varming AR, Rasmussen LB, Husted GR, Olesen K, Grønnegaard C, Willaing I. Improving empowerment, motivation, and medical adherence in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial of a patient-centered intervention. Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, Piatt G, Palmisano G, Hawkins J, et al. Outcomes at 18 months from a community health worker and peer leader diabetes self-management program for Latino adults. Al Omar M, Hasan S, Palaian S, Mahameed S. The impact of a self-management educational program coordinated through WhatsApp on diabetes control. Pharmacy Practice Granada. Hailu FB, Moen A, Hjortdahl P. Diabetes self-management education DSME —Effect on knowledge, self-care behavior, and self-efficacy among type 2 diabetes patients in Ethiopia: a controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Utz SW, Williams IC, Jones R, Hinton I, Alexander G, Yan G, et al. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Gavgani RM, Poursharifi H, Aliasgarzadeh A. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. Fardaza FE, Heidari H, Solhi M. Effect of educational intervention based on locus of control structure of attribution theory on self-care behavior of patients with type II diabetes. Med J Islam Repub Iran. Güner TA, Coşansu G. The effect of diabetes education and short message service reminders on metabolic control and disease management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Jeong S, Lee M, Ji E. Effect of pharmaceutical care interventions on glycemic control in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. Schünemann HJ. Using Systematic Reviews in Guideline Development: The GRADE Approach. Systematic Reviews in Health Research: Meta-Analysis in Context. Res Synth Methods. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes UKPDS 35 : prospective observational study. Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. De Greef K, Deforche B, Tudor-Locke C, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Increasing physical activity in Belgian type 2 diabetes patients: a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. Kirk AF, Higgins LA, Hughes AR, Fisher BM, Mutrie N, Hillis S, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to study the effect of exercise consultation on the promotion of physical activity in people with Type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetic Medicine. Keywords: education and counseling, HbA1c, meta-analysis, type 2 diabetes, self-management, patient-centered care. Citation: Asmat K, Dhamani K, Gul R and Froelicher ES The effectiveness of patient-centered care vs. usual care in type 2 diabetes self-management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. During times of illness, it's also important to check your blood sugar often. Stick to your diabetes meal plan if you can. Eating as usual helps you control your blood sugar. Keep a supply of foods that are easy on your stomach. These include gelatin, crackers, soups, instant pudding and applesauce. Drink lots of water or other fluids that don't add calories, such as tea, to make sure you stay hydrated. If you take insulin, you may need to sip sugary drinks such as juice or sports drinks. These drinks can help keep your blood sugar from dropping too low. It's risky for some people with diabetes to drink alcohol. Alcohol can lead to low blood sugar shortly after you drink it and for hours afterward. The liver usually releases stored sugar to offset falling blood sugar levels. But if your liver is processing alcohol, it may not give your blood sugar the needed boost. Get your healthcare professional's OK to drink alcohol. With diabetes, drinking too much alcohol sometimes can lead to health conditions such as nerve damage. But if your diabetes is under control and your healthcare professional agrees, an occasional alcoholic drink is fine. Women should have no more than one drink a day. Men should have no more than two drinks a day. One drink equals a ounce beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1. Don't drink alcohol on an empty stomach. If you take insulin or other diabetes medicines, eat before you drink alcohol. This helps prevent low blood sugar. Or drink alcohol with a meal. Choose your drinks carefully. Light beer and dry wines have fewer calories and carbohydrates than do other alcoholic drinks. If you prefer mixed drinks, sugar-free mixers won't raise your blood sugar. Some examples of sugar-free mixers are diet soda, diet tonic, club soda and seltzer. Add up calories from alcohol. If you count calories, include the calories from any alcohol you drink in your daily count. Ask your healthcare professional or a registered dietitian how to make calories and carbohydrates from alcoholic drinks part of your diet plan. Check your blood sugar level before bed. Alcohol can lower blood sugar levels long after you've had your last drink. So check your blood sugar level before you go to sleep. The snack can counter a drop in your blood sugar. Changes in hormone levels the week before and during periods can lead to swings in blood sugar levels. Look for patterns. Keep careful track of your blood sugar readings from month to month. You may be able to predict blood sugar changes related to your menstrual cycle. Your healthcare professional may recommend changes in your meal plan, activity level or diabetes medicines. These changes can make up for blood sugar swings. Check blood sugar more often. If you're likely nearing menopause or if you're in menopause, talk with your healthcare professional. Ask whether you need to check your blood sugar more often. Also, be aware that menopause and low blood sugar have some symptoms in common, such as sweating and mood changes. So whenever you can, check your blood sugar before you treat your symptoms. That way you can confirm whether your blood sugar is low. Most types of birth control are safe to use when you have diabetes. But combination birth control pills may raise blood sugar levels in some people. It's very important to take charge of stress when you have diabetes. The hormones your body makes in response to prolonged stress may cause your blood sugar to rise. It also may be harder to closely follow your usual routine to manage diabetes if you're under a lot of extra pressure. Take control. Once you know how stress affects your blood sugar level, make healthy changes. Learn relaxation techniques, rank tasks in order of importance and set limits. Whenever you can, stay away from things that cause stress for you. Exercise often to help relieve stress and lower your blood sugar. Get help. Learn new ways to manage stress. You may find that working with a psychologist or clinical social worker can help. These professionals can help you notice stressors, solve stressful problems and learn coping skills. The more you know about factors that have an effect on your blood sugar level, the better you can prepare to manage diabetes. If you have trouble keeping your blood sugar in your target range, ask your diabetes healthcare team for help. There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview. Error Email field is required. Error Include a valid email address. To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail. You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox. Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission. Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press. This content does not have an English version. This content does not have an Arabic version. Appointments at Mayo Clinic Mayo Clinic offers appointments in Arizona, Florida and Minnesota and at Mayo Clinic Health System locations. Request Appointment. Diabetes management: How lifestyle, daily routine affect blood sugar. Products and services. Diabetes management: How lifestyle, daily routine affect blood sugar Diabetes management takes awareness. By Mayo Clinic Staff. Thank you for subscribing! Sorry something went wrong with your subscription Please, try again in a couple of minutes Retry. Show references Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — Diabetes Care. Nutrition overview. American Diabetes Association. Accessed Dec. Diabetes and mental health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Insulin, medicines, and other diabetes treatments. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Insulin storage and syringe safety. Diabetes diet, eating, and physical activity. Type 2 diabetes mellitus adult. Mayo Clinic; Wexler DJ. Initial management of hyperglycemia in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes and women. Planning for sick days. Diabetes: Managing sick days. Castro MR expert opinion. Mayo Clinic. Hypoglycemia low blood glucose. Blood glucose and exercise. Riddell MC. Exercise guidance in adults with diabetes mellitus. Colberg SR, et al. Palermi S, et al. The complex relationship between physical activity and diabetes: An overview. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. |

| Self-Management Model - RHIhub Diabetes Prevention Toolkit | That includes activities that get the heart pumping, such as walking, biking and swimming. Following a meal plan can be among the most challenging aspects of diabetes self-management. Menu Search. Includes a DSMES toolkit, technical assistance guide, policies, reports, and several case studies. One-year outcomes of diabetes self-management training among Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with diabetes. |

Self-care planning for successful diabetes control -

Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM, A. J Gen Intern Med. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, Bollinger ST, Butcher MK, Condon JE, et al.

World Health Organization. Diabetes action now: an initiative of the World Health Organization and the International Diabetes Federation Organization.

Mehravar F, Mansournia MA, Holakouie-Naieni K, Nasli-Esfahani E, Mansournia N, Almasi-Hashiani A. Associations between diabetes self-management and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Epidemiol Health. Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine: a professional evolution.

Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, Spiegal N, Campbell MJ. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials.

Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions.

Cochrane Collaboration. Review manager RevMan [computer program]. Copenhagen Nord Cochrane Cent. Baker KA, Weeks SM. An overview of systematic review.

J Perianesth Nurs. Williams GC, Lynch M, Glasgow RE. Computer-assisted intervention improves patient-centered diabetes care by increasing autonomy support.

Health Psychology. Taylor KI, Oberle KM, Crutcher RA, Norton PG. Promoting health in type 2 diabetes: nurse-physician collaboration in primary care. Biol Res Nurs. Scain SF, Friedman R, Gross JL, A. structured educational program improves metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Sacco WP, Malone JI, Morrison AD, Friedman A, Wells K. Effect of a brief, regular telephone intervention by paraprofessionals for type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med.

Carter EL, Nunlee-Bland G, Callender C. A patient-centric, provider-assisted diabetes telehealth self-management intervention for urban minorities. PubMed Abstract Google Scholar. Forjuoh SN, Bolin JN, Huber Jr JC, Vuong AM, Adepoju OE, Helduser JW, et al.

BMC Public Health. Yuan C, Lai CW, Chan LW, Chow M, Law HK, Ying M. The effect of diabetes self-management education on body weight, glycemic control, and other metabolic markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. Pérez-Escamilla R, Damio G, Chhabra J, et al.

Impact of a community health workers-led structured program on blood glucose control among Latinos with type 2 diabetes: the DIALBEST trial. Ebrahimi H, Sadeghi M, Amanpour F, Vahedi H.

Evaluation of empowerment model on indicators of metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, a randomized clinical trial study. Primary Care Diabetes. Jutterström L, Hörnsten Å, Sandström H, Stenlund H, Isaksson U. Nurse-led patient-centered self-management support improves HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes—a randomized study.

Patient Educ Couns. Windrum P, García-Goñi M, Coad H. The impact of patient-centered versus didactic education programs in chronic patients by severity: the case of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Value Health. Azami G, Soh KL, Sazlina SG, Salmiah M, Aazami S, Mozafari M, et al.

Effect of a nurse-led diabetes self-management education program on glycosylated hemoglobin among adults with type 2 diabetes. Abraham AM, Sudhir PM, Philip M, Bantwal G. Efficacy of a brief self-management intervention in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial from India.

Indian J Psychol Med. Cheng L, Sit JW, Choi KC, Chair SY, Li X, Wu Y, et al. Effectiveness of a patient-centred, empowerment-based intervention programme among patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial.

Int J Nurs Studies. Zheng F, Liu S, Liu Y, Deng L. Effects of an outpatient diabetes self-management education on patients with type 2 diabetes in China: a randomized controlled trial. Ing CT, Zhang G, Dillard A, Yoshimura SR, Hughes C, Palakiko DM.

Social support groups in the maintenance of glycemic control after community-based intervention. Varming AR, Rasmussen LB, Husted GR, Olesen K, Grønnegaard C, Willaing I. Improving empowerment, motivation, and medical adherence in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial of a patient-centered intervention.

Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, Piatt G, Palmisano G, Hawkins J, et al. Outcomes at 18 months from a community health worker and peer leader diabetes self-management program for Latino adults.

Al Omar M, Hasan S, Palaian S, Mahameed S. The impact of a self-management educational program coordinated through WhatsApp on diabetes control.

Pharmacy Practice Granada. Hailu FB, Moen A, Hjortdahl P. Diabetes self-management education DSME —Effect on knowledge, self-care behavior, and self-efficacy among type 2 diabetes patients in Ethiopia: a controlled clinical trial.

Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Utz SW, Williams IC, Jones R, Hinton I, Alexander G, Yan G, et al. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes.

Gavgani RM, Poursharifi H, Aliasgarzadeh A. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. Fardaza FE, Heidari H, Solhi M. Effect of educational intervention based on locus of control structure of attribution theory on self-care behavior of patients with type II diabetes.

Med J Islam Repub Iran. Güner TA, Coşansu G. The effect of diabetes education and short message service reminders on metabolic control and disease management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Jeong S, Lee M, Ji E. Effect of pharmaceutical care interventions on glycemic control in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. Schünemann HJ. Using Systematic Reviews in Guideline Development: The GRADE Approach. Systematic Reviews in Health Research: Meta-Analysis in Context.

Res Synth Methods. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes UKPDS 35 : prospective observational study.

Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. De Greef K, Deforche B, Tudor-Locke C, De Bourdeaudhuij I.

Increasing physical activity in Belgian type 2 diabetes patients: a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. Kirk AF, Higgins LA, Hughes AR, Fisher BM, Mutrie N, Hillis S, et al.

A randomized, controlled trial to study the effect of exercise consultation on the promotion of physical activity in people with Type 2 diabetes: a pilot study.

Diabetic Medicine. Keywords: education and counseling, HbA1c, meta-analysis, type 2 diabetes, self-management, patient-centered care. Citation: Asmat K, Dhamani K, Gul R and Froelicher ES The effectiveness of patient-centered care vs.

usual care in type 2 diabetes self-management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Received: 15 July ; Accepted: 03 October ; Published: 28 October Copyright © Asmat, Dhamani, Gul and Froelicher.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY. The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author s and the copyright owner s are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice.

No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers.

Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Top bar navigation. In the Netherlands, diabetes care is of high quality as indicated by the excellent Euro Diabetes Index-scores concerning, amongst other, multidisciplinary collaboration and coordination between healthcare providers [ 2 ]. Findings from previous research suggest that patients with adequate glycaemic control are able to maintain this level of control when the frequency of consultations with health professionals is reduced, for example from 3-monthly to 6-monthly monitoring [ 4 ].

As complications of T2DM are strongly associated with an unhealthy lifestyle [ 5 , 6 , 7 ] focusing on self-management, including lifestyle change, may be a more efficient treatment strategy for healthcare providers as well as patients.

Self-management is defined as the active participation of patients in their treatment [ 8 ]. According to Corbin and Strauss [ 9 ], self-management comprises three distinct sets of activities: 1 medical management, e. taking medication and adhering to dietary advice; 2 behavioural management, e.

adopting new behaviours in the context of a chronic disease; and 3 emotional management, e. dealing with the feelings of frustration, fright, and despair associated with chronic disease. Since T2DM is a chronic disease and patients only see health professionals a few times a year, patients themselves need to be in control of all these aspects for the remainder of time.

Self-management support is one of the essential components of the Chronic Care Model, a well-known guide to improve the management of chronic conditions [ 10 ].

Previous research has shown that successful support of self-management of patients with T2DM can have a positive impact on their lifestyle and, ultimately, result in improved health outcomes [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. However, international comparative research [ 16 ] also shows that self-management support remains relatively underdeveloped in most countries.

Moreover, it is often developed from the perspective of health professionals and care providers, rather than patients. It is expected that adequate self-management support improves health outcomes and efficiency of care [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Therefore, the objective of this study is to gain a better understanding on the perspectives of patients with T2DM regarding self-management support.

The aim of the PROFILe project is to determine optimal treatment strategies for subgroups of patients with T2DM with similar care needs, preferences and abilities, taking into account both clinical and non-clinical aspects [ 20 ].

As part of the PROFILe project, opportunities for improving self-management support for patients with T2DM were explored in this study. No ethical approval was needed for the study; as the participants were not physically involved in the research and the questionnaires were not mentally exhausting, the study was not subject to the Dutch Medical Research Human Subject Act.

All patients participating in the study gave written informed consent. Therefore, patients from this specific group were targeted in this research.

Accordingly, patients were included if they: 1 were diagnosed with T2DM no longer than five years ago; 2 made use of diabetes-related care provided by Dutch primary care; and 3 had a stable, adequate glycaemic control i. Patients received a monetary reimbursement for participating in the research.

Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent. Patients were invited to prepare themselves for the interviews by filling out so-called sensitising booklets [ 23 ]. The aim of the exercises in the booklets was to trigger participants to reflect on their experiences with self-management of diabetes.

An example of one of the pages from the sensitising booklet is shown in Fig. The use of sensitising booklets is a well-known tool within the domain of user-centred design research, i. a design research approach which emphasises user involvement throughout the design research process.

Using sensitizing booklets enables the researcher to quickly engage with the interviewee, prepares the interviewee for the interview, and allows for elaboration on specific topics that were mapped prior to the interview. This way, a deeper tacit or latent layer of information about the perspective of the patient can be addressed during the interviews [ 23 ].

Example page from the sensitising booklet in Dutch. The blue stickers were used to indicate moments in the day where the participant felt he or she had to take diabetes into account. During the interview, the participant was asked to explain how diabetes was taken into account in these moments, and how the participant experienced this.

Next, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted by the first author from March to April The researcher prepared a set of interview questions aligned with the exercises in the sensitising booklet. These aspects were written down and ranked by the participant according to impact on daily life scale 1 least — 5 most.

The full list of interview questions is presented in Additional file 1. The interviews were voice recorded for analysis. The interviews were analysed in four steps. First, voice recordings of the interviews were listened back, while making notes of the answers of all participants for each of the five topics of the booklet.

In the second step these notes were condensed to create statements within each of the topics according to a general inductive approach [ 24 ]. Third, the statements were discussed with the co-authors and categorized as concerning: 1 elements of self-management e.

exercising, knowledge, being in control ; 2 characteristics of the disease and treatment e. type of medication, diet, use of blood sugar level meter ; and 3 characteristics of the attitude towards the disease e.

acceptance, consequences, role of health professional vs. role of patient. Taking into account the objective of this paper, only the results of the first category will be presented. Sixteen people applied for participation in the study. Ten people Mean HbA1c was All participants were treated for T2DM by a general practitioner GP and practice nurse specialized in diabetes care at the GP practice.

Self-management is a term which is commonly used by health professionals. Rather, they felt they dealt with their daily life as it is now, just as every other person with or without T2DM.

But, apart from that, diabetes is not difficult; you just need to learn how to deal with it. Participants did not often experience problems caused by deteriorated glycaemic control, and therefore did not consider themselves as having to actively self-manage their disease. Although self-management was generally described as diabetes in daily life , participants also mentioned that if glycaemic control was no longer stable, a need for active self-management emerged.

They described that at such times, actions were required to prevent complications. However, over time, new lifestyles became part of their routine in daily life and were no longer experienced as active self-management.

Over time, active self-management changes into routine in daily life. When problems occur, patients shift back to active self-management grey peaks. All patients mentioned that T2DM influenced their daily life. Yet, the impact of T2DM on daily activities was greater for some patients than for others.

Whether patients considered diabetes to have a large impact on their daily life also seemed to influence their acceptance of diabetes and the new lifestyle. Some patients felt that diabetes had to be taken into account at all times.

The health professional gives advice, but you have to do the work and decide what to eat and drink and what not. Since patients experienced diabetes in daily life rather than self-management , aspects which influence diabetes in daily life were investigated. The aspects scored by the participants on a five-point scale that had the most impact 4 or 5 out of 5 on the daily life of T2DM patients were categorised and are shown in Table 2.

To account for these different aspects patients felt required to be in control, and to have sufficient knowledge to keep control. Participants mentioned very specific things that made them feel supported. For example, with regard to exercising, patients felt supported by their dog or children.

However, patients were not able to mention specific causes for not feeling supported. For example, concerning exercise, they mentioned a lack of support in motivation.

Overall, patients felt supported in self-management in some ways, but mainly felt as if they had to find out everything about living with diabetes on their own. In their view, health professionals provide medical advice, but could not explain how to deal with T2DM in daily life.

The daily care for type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM mostly comes down to the person suffering from it. To maintain adequate glycaemic control, patients with T2DM have to make many decisions and fulfil complex care activities every day [ 25 ]. Respondents in our study mentioned a need to gain knowledge, be in control, adapt their diet, exercise, maintain a regular schedule, and adhere to complex medication regimes.

However, in fulfilling these responsibilities, they did not view themselves as actively participating in their treatment, at least not continuously. This is in line with previous research indicating that patients who perceive their illness as stable have different needs for support than patients who experience their disease as episodic or progressively deteriorating [ 26 ].

An unpredictable course of illness can cause feelings of lower self-efficacy, i. patients might experience their self-management as unsuccessful and, as a result, feel a greater need for support [ 27 , 28 ]. Although overall, respondents did not experience themselves as actively managing their diabetes, they did identify two time points of active self-management during their illness course, particularly in the period after diagnosis and when problems occurred.

With regard to support for their self-management, patients expressed that they did not feel optimally supported, which is in line with findings from previous studies [ 16 , 29 ]. However, they had difficulties in describing what is lacking, suggesting that they do not know what exactly is missing or how support could be improved.

Self-management needs to be supported in order to more successfully treat T2DM [ 30 ]. This person-centred perspective is valuable, as patients are expected to be in control of management of T2DM in daily life. Therefore, outcomes of this research can be used to develop tools and strategies that support self-management in a way that better fits the needs of T2DM patients.

The development of tools and strategies from the perspective of the user i. It may also improve cost-effectiveness of the intervention, as costly implementation of features that patients do not want or cannot use is avoided [ 31 ]. Our findings suggest two aspects that are important to consider in developing user-centred self-management support interventions for patients with T2DM.

First, it is important to provide support at the right moments, i. when patients experience a need for support due to changes in their daily routines or changes in their health. Two such moments were identified in our study: the period directly after diagnosis and at instances when problems occur glycaemic control deteriorates.

In addition to physical limitations, such as pain and fatigue, which further complicate self-management, deterioration of health can cause feelings of loss of control, and disappointment that previous self-management strategies have failed. At such moments, patients might be more open to professional support to make sustainable behavioural change to maintain glycaemic control, and prevent — or at least postpone — the debilitating long-term complications of insufficient glycaemic control.

Second, it is important to provide support for relevant element s , i. By taking into account these specific topics when developing tools and strategies, patients will be better supported and therefore better able to successfully self-manage their disease. An important strength of this research is its focus outside medical context.

The research addressed the participant as a person with T2DM , not as a patient. This way, participants expressed they felt comfortable in sharing their experiences regarding T2DM and self-management. Participants mentioned that within the medical context, they fear being criticised on the way they cope with the disease as health professionals mostly focus on HbA1c values and less on the T2DM-related issues of the patient.

Patients were triggered to think about their personal experiences regarding management of and dealing with T2DM prior to the interview. Therefore, the researcher could touch upon a deeper layer of information during the interviews.

This study explored self-management and self-management support needs from the perspective of patients with T2DM rather than health professionals. We focused particularly on the subgroup of patients with a recent diagnosis and stable, adequate glycaemic control, for whom self-management support may be a more cost-effective- and efficient treatment approach than provider-led care.

However, patients who have not yet achieved stable, adequate glycaemic control may have different support needs, which should be explored in further detail.

Furthermore, the sample size was sufficient for the current qualitative study, as the aim was to get detailed insights into the experiences of individuals. Nevertheless, to assess the generalizability of findings, it is important to replicate the current study with a larger sample of patients.

This may require different methodology as well. However, this methodology is less applicable to theory and model building [ 24 ]. During the time of the coronavirus disease COVID pandemic, reimbursement policies have changed professional. For many individuals with diabetes, the most challenging part of the treatment plan is determining what to eat.

Nutrition therapy plays an integral role in overall diabetes management, and each person with diabetes should be actively engaged in education, self-management, and treatment planning with his or her health care team, including the collaborative development of an individualized eating plan 56 , See Table 5.

Because of the progressive nature of type 2 diabetes, behavior modification alone may not be adequate to maintain euglycemia over time.

To promote and support healthful eating patterns, emphasizing a variety of nutrient-dense foods in appropriate portion sizes, to improve overall health and: achieve and maintain body weight goals. To address individual nutrition needs based on personal and cultural preferences, health literacy and numeracy, access to healthful foods, willingness and ability to make behavioral changes, and existing barriers to change.

To maintain the pleasure of eating by providing nonjudgmental messages about food choices while limiting food choices only when indicated by scientific evidence. To provide an individual with diabetes the practical tools for developing healthy eating patterns rather than focusing on individual macronutrients, micronutrients, or single foods.

Management and reduction of weight is important for people with type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, or prediabetes with overweight or obesity. Lifestyle intervention programs should be intensive and have frequent follow-up to achieve significant reductions in excess body weight and improve clinical indicators.

People with prediabetes at a healthy weight should also be considered for behavioral interventions to help establish routine aerobic and resistance exercise 76 , 79 , 80 , as well as to establish healthy eating patterns.

It should be noted, however, that the clinical benefits of weight loss are progressive, and more intensive weight loss goals i. Overweight and obesity are also increasingly prevalent in people with type 1 diabetes and present clinical challenges regarding diabetes treatment and CVD risk factors 86 , Sustaining weight loss can be challenging 81 , 88 but has long-term benefits; maintaining weight loss for 5 years is associated with sustained improvements in A1C and lipid levels Along with routine medical management visits, people with diabetes and prediabetes should be screened during DSMES and MNT encounters for a history of dieting and past or current disordered eating behaviors.

Nutrition therapy should be individualized to help address maladaptive eating behavior e. For example, caloric restriction may be essential for glycemic control and weight maintenance, but rigid meal plans may be contraindicated for individuals who are at increased risk of clinically significant maladaptive eating behaviors If clinically significant eating disorders are identified during screening with diabetes-specific questionnaires, individuals should be referred to a mental health professional as needed 1.

Studies have demonstrated that a variety of eating plans, varying in macronutrient composition, can be used effectively and safely in the short term 1—2 years to achieve weight loss in people with diabetes. These plans include structured low-calorie meal plans with meal replacements 82 , 89 , 91 , a Mediterranean-style eating pattern 92 , and low-carbohydrate meal plans with additional support 93 , However, no single approach has been proven to be consistently superior 56 , 95 — 97 , and more data are needed to identify and validate those meal plans that are optimal with respect to long-term outcomes and patient acceptability.

The importance of providing guidance on an individualized meal plan containing nutrient-dense foods, such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, dairy, lean sources of protein including plant-based sources as well as lean meats, fish, and poultry , nuts, seeds, and whole grains, cannot be overemphasized 96 , as well as guidance on achieving the desired energy deficit 98 — Any approach to meal planning should be individualized considering the health status, personal preferences, and ability of the person with diabetes to sustain the recommendations in the plan.

Evidence suggests that there is not an ideal percentage of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and fat for people with diabetes. Therefore, macronutrient distribution should be based on an individualized assessment of current eating patterns, preferences, and metabolic goals. Dietary guidance should emphasize the importance of a healthy dietary pattern as a whole rather than focusing on individual nutrients, foods, or food groups, given that individuals rarely eat foods in isolation.

Personal preferences e. Members of the health care team should complement MNT by providing evidence-based guidance that helps people with diabetes make healthy food choices that meet their individualized needs and improve overall health. A variety of eating patterns are acceptable for the management of diabetes 56 , — Until the evidence surrounding comparative benefits of different eating patterns in specific individuals strengthens, health care providers should focus on the key factors that are common among the patterns: 1 emphasize nonstarchy vegetables, 2 minimize added sugars and refined grains, and 3 choose whole foods over highly processed foods to the extent possible The Mediterranean-style , — , low-carbohydrate — , and vegetarian or plant-based , , , eating patterns are all examples of healthful eating patterns that have shown positive results in research for individuals with type 2 diabetes, but individualized meal planning should focus on personal preferences, needs, and goals.

There is currently inadequate research in type 1 diabetes to support one eating pattern over another. For individuals with type 2 diabetes not meeting glycemic targets or for whom reducing glucose-lowering drugs is a priority, reducing overall carbohydrate intake with a low- or very-low-carbohydrate eating pattern is a viable option — As research studies on low-carbohydrate eating plans generally indicate challenges with long-term sustainability , it is important to reassess and individualize meal plan guidance regularly for those interested in this approach.

Efforts to modify habitual eating patterns are often unsuccessful in the long term; people generally go back to their usual macronutrient distribution Thus, the recommended approach is to individualize meal plans with a macronutrient distribution that is more consistent with personal preference and usual intake to increase the likelihood for long-term maintenance.

The diabetes plate method is a commonly used visual approach for providing basic meal planning guidance. Carbohydrate counting is a more advanced skill that helps plan for and track how much carbohydrate is consumed at meals and snacks.

Meal planning approaches should be customized to the individual, including their numeracy and food literacy level. Food literacy generally describes proficiency in food-related knowledge and skills that ultimately impact health, although specific definitions vary across initiatives , Studies examining the ideal amount of carbohydrate intake for people with diabetes are inconclusive, although monitoring carbohydrate intake and considering the blood glucose response to dietary carbohydrate are key for improving postprandial glucose management , The literature concerning glycemic index and glycemic load in individuals with diabetes is complex, often with varying definitions of low and high glycemic index foods , The glycemic index ranks carbohydrate foods on their postprandial glycemic response, and glycemic load takes into account both the glycemic index of foods and the amount of carbohydrate eaten.

Studies have found mixed results regarding the effect of glycemic index and glycemic load on fasting glucose levels and A1C, with one systematic review finding no significant impact on A1C , while two others demonstrated A1C reductions of 0.

Reducing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated evidence for improving glycemia and may be applied in a variety of eating patterns that meet individual needs and preferences For people with type 2 diabetes, low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate eating patterns, in particular, have been found to reduce A1C and the need for antihyperglycemic medications 56 , , , — Part of the challenge in interpreting low-carbohydrate research has been due to the wide range of definitions for a low-carbohydrate eating plan , Weight reduction was also a goal in many low-carbohydrate studies, which further complicates evaluating the distinct contribution of the eating pattern 41 , 93 , 97 , Providers should maintain consistent medical oversight and recognize that insulin and other diabetes medications may need to be adjusted to prevent hypoglycemia; and blood pressure will need to be monitored.

In addition, very-low-carbohydrate eating plans are not currently recommended for women who are pregnant or lactating, children, people who have renal disease, or people with or at risk for disordered eating, and these plans should be used with caution in those taking sodium—glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors because of the potential risk of ketoacidosis , Regardless of amount of carbohydrate in the meal plan, focus should be placed on high-quality, nutrient-dense carbohydrate sources that are high in fiber and minimally processed.

Both children and adults with diabetes are encouraged to minimize intake of refined carbohydrates with added sugars, fat, and sodium and instead focus on carbohydrates from vegetables, legumes, fruits, dairy milk and yogurt , and whole grains. Regular intake of sufficient dietary fiber is associated with lower all-cause mortality in people with diabetes , , and prospective cohort studies have found dietary fiber intake is inversely associated with risk of type 2 diabetes — The consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and processed food products with high amounts of refined grains and added sugars is strongly discouraged , — , as these have the capacity to displace healthier, more nutrient-dense food choices.

Individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes taking insulin at mealtime should be offered intensive and ongoing education on the need to couple insulin administration with carbohydrate intake. For people whose meal schedule or carbohydrate consumption is variable, regular education to increase understanding of the relationship between carbohydrate intake and insulin needs is important.

In addition, education on using insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios for meal planning can assist individuals with effectively modifying insulin dosing from meal to meal to improve glycemic management , , — Studies have shown that dietary fat and protein can impact early and delayed postprandial glycemia — , and it appears to have a dose-dependent response — Results from high-fat, high-protein meal studies highlight the need for additional insulin to cover these meals; however, more studies are needed to determine the optimal insulin dose and delivery strategy.

The effectiveness of insulin dosing decisions should be confirmed with a structured approach to blood glucose monitoring or continuous glucose monitoring to evaluate individual responses and guide insulin dose adjustments. Checking glucose 3 h after eating may help to determine if additional insulin adjustments are required i.

Food literacy, numeracy, interest, and capability should be evaluated For individuals on a fixed daily insulin schedule, meal planning should emphasize a relatively fixed carbohydrate consumption pattern with respect to both time and amount, while considering insulin action.

Attention to resultant hunger and satiety cues will also help with nutrient modifications throughout the day 56 , There is no evidence that adjusting the daily level of protein intake typically 1—1.

Therefore, protein intake goals should be individualized based on current eating patterns. Reducing the amount of dietary protein below the recommended daily allowance of 0. In individuals with type 2 diabetes, protein intake may enhance or increase the insulin response to dietary carbohydrates Therefore, use of carbohydrate sources high in protein such as milk and nuts to treat or prevent hypoglycemia should be avoided due to the potential concurrent rise in endogenous insulin.

Providers should counsel patients to treat hypoglycemia with pure glucose i. The ideal amount of dietary fat for individuals with diabetes is controversial. The type of fats consumed is more important than total amount of fat when looking at metabolic goals and CVD risk, and it is recommended that the percentage of total calories from saturated fats should be limited 92 , , — Multiple RCTs including patients with type 2 diabetes have reported that a Mediterranean-style eating pattern 92 , — , rich in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats, can improve both glycemic management and blood lipids.

Evidence does not conclusively support recommending n-3 eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA] supplements for all people with diabetes for the prevention or treatment of cardiovascular events 56 , , In individuals with type 2 diabetes, two systematic reviews with n-3 and n-6 fatty acids concluded that the dietary supplements did not improve glycemic management , People with diabetes should be advised to follow the guidelines for the general population for the recommended intakes of saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and trans fat Trans fats should be avoided.

In addition, as saturated fats are progressively decreased in the diet, they should be replaced with unsaturated fats and not with refined carbohydrates Sodium recommendations should take into account palatability, availability, affordability, and the difficulty of achieving low-sodium recommendations in a nutritionally adequate diet There continues to be no clear evidence of benefit from herbal or nonherbal i.

Metformin is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency per a report from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study DPPOS , suggesting that periodic testing of vitamin B12 levels should be considered in patients taking metformin, particularly in those with anemia or peripheral neuropathy Routine supplementation with antioxidants, such as vitamins E and C and carotene, is not advised due to lack of evidence of efficacy and concern related to long-term safety.

In addition, there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of herbal supplements and micronutrients, such as cinnamon , curcumin, vitamin D , aloe vera, or chromium, to improve glycemia in people with diabetes 56 , Although the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes D2d prospective RCT showed no significant benefit of vitamin D versus placebo on the progression to type 2 diabetes in individuals at high risk , post hoc analyses and meta-analyses suggest a potential benefit in specific populations — Further research is needed to define patient characteristics and clinical indicators where vitamin D supplementation may be of benefit.

For special populations, including pregnant or lactating women, older adults, vegetarians, and people following very-low-calorie or low-carbohydrate diets, a multivitamin may be necessary.

Moderate alcohol intake does not have major detrimental effects on long-term blood glucose management in people with diabetes. People with diabetes should be educated about these risks and encouraged to monitor blood glucose frequently after drinking alcohol to minimize such risks.

People with diabetes can follow the same guidelines as those without diabetes if they choose to drink. For women, no more than one drink per day, and for men, no more than two drinks per day is recommended one drink is equal to a oz beer, a 5-oz glass of wine, or 1.

The U. Food and Drug Administration has approved many nonnutritive sweeteners for consumption by the general public, including people with diabetes 56 , For some people with diabetes who are accustomed to regularly consuming sugar-sweetened products, nonnutritive sweeteners containing few or no calories may be an acceptable substitute for nutritive sweeteners those containing calories, such as sugar, honey, and agave syrup when consumed in moderation , Nonnutritive sweeteners do not appear to have a significant effect on glycemic management , , , but they can reduce overall calorie and carbohydrate intake , as long as individuals are not compensating with additional calories from other food sources 56 , There is mixed evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses for nonnutritive sweetener use with regard to weight management, with some finding benefit in weight loss — , while other research suggests an association with weight gain The addition of nonnutritive sweeteners to diets poses no benefit for weight loss or reduced weight gain without energy restriction Low-calorie or nonnutritive-sweetened beverages may serve as a short-term replacement strategy; however, people with diabetes should be encouraged to decrease both sweetened and nonnutritive-sweetened beverages, with an emphasis on water intake Additionally, some research has found that higher nonnutritive-sweetened beverage and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption may be associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, although substantial heterogeneity makes interpreting the results difficult — B Prolonged sitting should be interrupted every 30 min for blood glucose benefits.

Yoga and tai chi may be included based on individual preferences to increase flexibility, muscular strength, and balance. Promote increase in nonsedentary activities above baseline for sedentary individuals with type 1 E and type 2 B diabetes.

Examples include walking, yoga, housework, gardening, swimming, and dancing. Physical activity is a general term that includes all movement that increases energy use and is an important part of the diabetes management plan.

Exercise is a more specific form of physical activity that is structured and designed to improve physical fitness. Both physical activity and exercise are important. Exercise has been shown to improve blood glucose control, reduce cardiovascular risk factors, contribute to weight loss, and improve well-being Physical activity is as important for those with type 1 diabetes as it is for the general population, but its specific role in the prevention of diabetes complications and the management of blood glucose is not as clear as it is for those with type 2 diabetes.

A recent study suggested that the percentage of people with diabetes who achieved the recommended exercise level per week min varied by race. Objective measurement by accelerometer showed that It is important for diabetes care management teams to understand the difficulty that many patients have reaching recommended treatment targets and to identify individualized approaches to improve goal achievement.

Moderate to high volumes of aerobic activity are associated with substantially lower cardiovascular and overall mortality risks in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes A recent prospective observational study of adults with type 1 diabetes suggested that higher amounts of physical activity led to reduced cardiovascular mortality after a mean follow-up time of There are also considerable data for the health benefits e.

of regular exercise for those with type 1 diabetes A recent study suggested that exercise training in type 1 diabetes may also improve several important markers such as triglyceride level, LDL, waist circumference, and body mass In adults with type 2 diabetes, higher levels of exercise intensity are associated with greater improvements in A1C and in cardiorespiratory fitness ; sustained improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and weight loss have also been associated with a lower risk of heart failure Other benefits include slowing the decline in mobility among overweight patients with diabetes Increased physical activity soccer training has also been shown to be beneficial for improving overall fitness in Latino men with obesity, demonstrating feasible methods to increase physical activity in an often hard-to-engage population Physical activity and exercise should be recommended and prescribed to all individuals who are at risk for or with diabetes as part of management of glycemia and overall health.

Specific recommendations and precautions will vary by the type of diabetes, age, activity done, and presence of diabetes-related health complications. Recommendations should be tailored to meet the specific needs of each individual All children, including children with diabetes or prediabetes, should be encouraged to engage in regular physical activity.

Children should engage in at least 60 min of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity every day, with muscle- and bone-strengthening activities at least 3 days per week In general, youth with type 1 diabetes benefit from being physically active, and an active lifestyle should be recommended to all Youth with type 1 diabetes who engage in more physical activity may have better health outcomes and health-related quality of life , People with diabetes should perform aerobic and resistance exercise regularly Daily exercise, or at least not allowing more than 2 days to elapse between exercise sessions, is recommended to decrease insulin resistance, regardless of diabetes type , A study in adults with type 1 diabetes found a dose-response inverse relationship between self-reported bouts of physical activity per week and A1C, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes-related complications such as hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, retinopathy, and microalbuminuria Many adults, including most with type 2 diabetes, may be unable or unwilling to participate in such intense exercise and should engage in moderate exercise for the recommended duration.

Although heavier resistance training with free weights and weight machines may improve glycemic control and strength , resistance training of any intensity is recommended to improve strength, balance, and the ability to engage in activities of daily living throughout the life span.

Providers and staff should help patients set stepwise goals toward meeting the recommended exercise targets. As individuals intensify their exercise program, medical monitoring may be indicated to ensure safety and evaluate the effects on glucose management. See the section physical activity and glycemic control below.

Recent evidence supports that all individuals, including those with diabetes, should be encouraged to reduce the amount of time spent being sedentary—waking behaviors with low energy expenditure e. Participating in leisure-time activity and avoiding extended sedentary periods may help prevent type 2 diabetes for those at risk , and may also aid in glycemic control for those with diabetes.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found higher frequency of regular leisure-time physical activity was more effective in reducing A1C levels A wide range of activities, including yoga, tai chi, and other types, can have significant impacts on A1C, flexibility, muscle strength, and balance , — Flexibility and balance exercises may be particularly important in older adults with diabetes to maintain range of motion, strength, and balance Clinical trials have provided strong evidence for the A1C-lowering value of resistance training in older adults with type 2 diabetes and for an additive benefit of combined aerobic and resistance exercise in adults with type 2 diabetes If not contraindicated, patients with type 2 diabetes should be encouraged to do at least two weekly sessions of resistance exercise exercise with free weights or weight machines , with each session consisting of at least one set group of consecutive repetitive exercise motions of five or more different resistance exercises involving the large muscle groups For type 1 diabetes, although exercise in general is associated with improvement in disease status, care needs to be taken in titrating exercise with respect to glycemic management.

Each individual with type 1 diabetes has a variable glycemic response to exercise. This variability should be taken into consideration when recommending the type and duration of exercise for a given individual Women with preexisting diabetes, particularly type 2 diabetes, and those at risk for or presenting with gestational diabetes mellitus should be advised to engage in regular moderate physical activity prior to and during their pregnancies as tolerated However, providers should perform a careful history, assess cardiovascular risk factors, and be aware of the atypical presentation of coronary artery disease, such as recent patient-reported or tested decrease in exercise tolerance, in patients with diabetes.

Certainly, high-risk patients should be encouraged to start with short periods of low-intensity exercise and slowly increase the intensity and duration as tolerated. Providers should assess patients for conditions that might contraindicate certain types of exercise or predispose to injury, such as uncontrolled hypertension, untreated proliferative retinopathy, autonomic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy, and a history of foot ulcers or Charcot foot.

Those with complications may need a more thorough evaluation prior to starting an exercise program , In some patients, hypoglycemia after exercise may occur and last for several hours due to increased insulin sensitivity.

Hypoglycemia is less common in patients with diabetes who are not treated with insulin or insulin secretagogues, and no routine preventive measures for hypoglycemia are usually advised in these cases. Intense activities may actually raise blood glucose levels instead of lowering them, especially if pre-exercise glucose levels are elevated Because of the variation in glycemic response to exercise bouts, patients need to be educated to check blood glucose levels before and after periods of exercise and about the potential prolonged effects depending on intensity and duration see the section diabetes self-management education and support above.

If proliferative diabetic retinopathy or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is present, then vigorous-intensity aerobic or resistance exercise may be contraindicated because of the risk of triggering vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment Consultation with an ophthalmologist prior to engaging in an intense exercise regimen may be appropriate.